[Reprinted

from SUSRIS]

Hundreds

of thousands of Muslims flooded the ports of

entry in western Saudi Arabia this week to start

the pilgrimage to Makkah. On the occasion

of the Hajj, we are pleased to present this

essay from Dr. David E. Long which appeared in

the Saudi-American

Forum in February 2003. This essay

will be followed by a previously published interview with Dr. Long

on the subject of the Hajj.

["Standing Day" will be observed on

Friday, December 29, 2006. The four-day Eid al Adha will

start on Saturday, December 30, 2006]

Executive

Summary

Each

year, 2 million Muslims perform the Hajj, or

Great Pilgrimage to Makkah. One of the Five

Pillars of Islam, the Hajj is required of all

believers once in their lifetimes provided they

are physically, mentally and financially able.

Each

year, 2 million Muslims perform the Hajj, or

Great Pilgrimage to Makkah. One of the Five

Pillars of Islam, the Hajj is required of all

believers once in their lifetimes provided they

are physically, mentally and financially able.

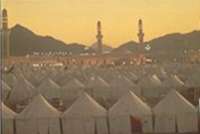

For the

duration of the Hajj and the traditional visit

to al-Madinah afterward, the Saudi government

must insure that the Hajjis are provided with

adequate housing (mainly in tents), food, water,

health and sanitation, ground transportation,

and public safety and security.

The

government has spent billions of dollars on Hajj

infrastructure from the two special Hajj air

terminals which are the largest structures under

a single roof in the world, to the extensive

preventative and curative health and sanitation

facilities at all the major Hajj locations. The

Saudi government has also maintained a strict

policy banning political activity so that

militants do not desecrate this peaceful and

joyous occasion. It is a task of almost

unimaginable proportions.

The

Hajj and Its Impact on Saudi Arabia

and the Muslim World

By

David E. Long

Each year,

2 million Muslims perform the Hajj, or Great

Pilgrimage to Makkah, the birthplace of the

Prophet Muhammad and where the Qur'an was first

revealed to him. One of the Five Pillars of

Islam,1 the Hajj is

required of all believers once in their

lifetimes provided they are physically, mentally

and financially able. Sura (Chapter) 3: 90-91 of

the Qur'an states: "And the Pilgrimage to

the Temple (the Hajj) is an obligation to God

from those who are able to journey there."

Although it is not technically a part of the

Hajj, most Hajjis then visit al-Madinah, 450

kilometers to the north. In 622 AD, Muhammad and

his followers fled to al-Madinah from mounting

persecution in Makkah. The flight, known as the

Hijrah, marks the beginning of the Muslim, or

Hijriyyah calendar.2

Many of the chapters (suras) of the Qur'an were

written down in al-Madinah.

Each year,

2 million Muslims perform the Hajj, or Great

Pilgrimage to Makkah, the birthplace of the

Prophet Muhammad and where the Qur'an was first

revealed to him. One of the Five Pillars of

Islam,1 the Hajj is

required of all believers once in their

lifetimes provided they are physically, mentally

and financially able. Sura (Chapter) 3: 90-91 of

the Qur'an states: "And the Pilgrimage to

the Temple (the Hajj) is an obligation to God

from those who are able to journey there."

Although it is not technically a part of the

Hajj, most Hajjis then visit al-Madinah, 450

kilometers to the north. In 622 AD, Muhammad and

his followers fled to al-Madinah from mounting

persecution in Makkah. The flight, known as the

Hijrah, marks the beginning of the Muslim, or

Hijriyyah calendar.2

Many of the chapters (suras) of the Qur'an were

written down in al-Madinah.

Although

many religions have pilgrimages, the Hajj is

virtually unique in its worldwide participation

and sheer size. It is hard for anyone who has

not been in the Kingdom during the Hajj to

appreciate its full scope. How can a country

with a relatively small population such as Saudi

Arabia maintain such a good record in

administering it each year? The following is a

brief overview of administrative, political,

economic, and social significance of the Hajj on

Saudi Arabia and indeed the entire Muslim world.

But first, for those not familiar with the rites

of the Hajj, it would be instructive follow the

pilgrims through the rites.

The

Religious Significance of the Hajj

The

Hajj takes place each year during the month of

Dhu al-Hijja, the last month of the Muslim

calendar. It is virtually impossible to describe

the deep emotions generated during the Hajj,

even by watching it on Saudi television which

annually records it. Each rite has a special

significance. The principal rites are Ihram,

Tawaf, Sa`y, Wuquf, Nafrah, Rajm, and the `Id

al-Adha:3

Ihram

is a ritual cleansing and consecration and

declaration of intent to perform the Hajj,

performed before entering Makkah. Afterwards,

pilgrim don special Irham garb of white

terrycloth representing the equality of all

believers before God, regardless of race,

gender, age or social standing. Men wear two

coverings for the upper and lower body, and

women wear white robes but need not cover their

faces.

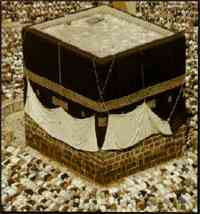

Tawaf,

performed on arrival in the great Haram

Mosque in Makkah, is completed by

circling seven times around the Ka`bah,

located in a great open area in the

Haram Mosque. The Ka`bah is considered

the spiritual and geographical center of

Islam, toward which Muslims face in

prayer. Tradition has it that the Ka`bah,

a dark stone structure, was originally

built by the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham)

and his son Ismail (Ishmael) as a place

of worship of the one true God, and

symbolizes monotheism which is at the

heart of Islam. Each year just before

the Hajj, the Ka`bah is covered with a

new black velvet and gold drape called

the Kiswah. Following the Arrival Tawaf,

pilgrims say prayers at the Maqam

Ibraham, a station near the Ka`bah, and

also drink water from the holy well of

Zamzam. Tradition has it that God

created the well by striking a stone so

that Hajar (Hagar) and Ismail might

drink when they were about to die of

thirst.

Tawaf,

performed on arrival in the great Haram

Mosque in Makkah, is completed by

circling seven times around the Ka`bah,

located in a great open area in the

Haram Mosque. The Ka`bah is considered

the spiritual and geographical center of

Islam, toward which Muslims face in

prayer. Tradition has it that the Ka`bah,

a dark stone structure, was originally

built by the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham)

and his son Ismail (Ishmael) as a place

of worship of the one true God, and

symbolizes monotheism which is at the

heart of Islam. Each year just before

the Hajj, the Ka`bah is covered with a

new black velvet and gold drape called

the Kiswah. Following the Arrival Tawaf,

pilgrims say prayers at the Maqam

Ibraham, a station near the Ka`bah, and

also drink water from the holy well of

Zamzam. Tradition has it that God

created the well by striking a stone so

that Hajar (Hagar) and Ismail might

drink when they were about to die of

thirst.

Sa`y

consists of seven laps on foot between two

elevations formerly adjacent to the mosque but

now a part of the mosque complex. It

commemorates Hagar's frantic search for water.

Sa`y and Tawaf together are called the Umrah

(Lesser pilgrimage) and can be performed any

time during the year but do not meet the

obligation of Hajj.

Wuquf

is performed in a ceremony of

"Standing" on the Plain of

Arafat, about 20 kilometers east of

Makkah beginning at noon on the ninth

day of Dhu al-Hijjah, called Yawm al-Wuquf,

"Standing Day." The favored

spot to stand is Jabal al-Rahma, the

Mount of Mercy, a rocky hill rising

about 150 feet above the plain and

crowned by a tall white stone obelisk.

According to Islamic tradition, the

Wuquf is the Hajj - the supreme hours.

Everyone must literally be present at

`Arafat at maghrib (sunset) or the Hajj

is forfeited.

Wuquf

is performed in a ceremony of

"Standing" on the Plain of

Arafat, about 20 kilometers east of

Makkah beginning at noon on the ninth

day of Dhu al-Hijjah, called Yawm al-Wuquf,

"Standing Day." The favored

spot to stand is Jabal al-Rahma, the

Mount of Mercy, a rocky hill rising

about 150 feet above the plain and

crowned by a tall white stone obelisk.

According to Islamic tradition, the

Wuquf is the Hajj - the supreme hours.

Everyone must literally be present at

`Arafat at maghrib (sunset) or the Hajj

is forfeited.

Nafrah:

The word literally means "the Rush" in

Arabic. As the sun finally disappears over the

horizon, in its wake some 2 million Hajjis surge

forth from `Arafat to Mina, some 17 kilometers

away. They travel by bus, car, truck, and for

many as an act of piety, by foot. With so many

people, the Nafrah is one of the most chaotic

and stressful exercises in this or any other

religious observance. The first stop is

Muzdalifa about seven kilometers west, where

Sunset and Evening prayers (Salat al-Maghrib and

al-`Isha) are traditionally said, and a special

prayer can be said at a roofless mosque called

al-Mash`ar al-Haram (the Sacred Grove). Because

of the great crowds, now only the earliest to

depart `Arafat usually arrive in Muzdalifa in

time for Maghrib prayer, and many say them

before leaving Arafat. After midnight and saying

Early Morning prayer (Salat al-Fajr), the Hajjis

travel on to Mina, a small town about ten

kilometers farther west, where they will stay

for three days.

Rajm:

In Mina, Hajjis perform Rajm over the next three

days, the ritual throwing of seven stones at

three pillars, called Jamras which represent

Shaytans (devils). The tenth through the twelfth

of Dhu al-Hijja is also the `Id al-Adha (the

Feast of the Sacrifice) which includes the

sacramental sacrifice of a blemishless animal,

usually a sheep. The `Id is celebrated not only

at the Hajj but also throughout the Muslim world

where it is a joyous time to visit family and

friends.

On the

thirteenth, Hajjis return to Makkah for a

Farewell Tawaf and are free from all Ihram

restrictions. At that point, the Hajj is

technically over, and Hajjis are free to travel

home or on to visit al-Madinah. There the pace

is more relaxed and people can take more time to

see the sights, principally the Prophet's

Mosque.

The

Impact of the Hajj on Saudi Public

Administration

Due

to tremendous advances in transportation and

communications technology, the Hajj has changed

more in the past eight decades since Saudi

Arabia formally became guardians of the Holy

Places in 1926 than it had in the previous 1300

years of Islamic history.4

In 1927, an estimated 300 to 350 thousand

attended with only about 150,000 from outside

the Kingdom. In 1972, there was a total of

1,042,007 Hajjis, including 353,460 Saudis,

209,208 non-Saudi residents, and 479,339 from

abroad.5 Today, an

estimated 2 million perform the Hajj.

The

unprecedented increase in the numbers of

pilgrims has greatly increased the

complexity of Hajj administration. Just

to make room for foreign Hajjis, the

Saudi government has restricted

attendance by Saudis, many of whom

formerly often attended every year, to

once every five years, and has

negotiated visa quotas for foreign

Hajjis with their countries of origin.

The

unprecedented increase in the numbers of

pilgrims has greatly increased the

complexity of Hajj administration. Just

to make room for foreign Hajjis, the

Saudi government has restricted

attendance by Saudis, many of whom

formerly often attended every year, to

once every five years, and has

negotiated visa quotas for foreign

Hajjis with their countries of origin.

Another

huge logistical problem is how to dispose of the

remains of the thousands of sheep annually

sacrificed at Mina. For years, families were

allowed to keep only what they consumed during

the `Id and the rest was buried in huge pits. In

recent years, however, an abattoir has been

constructed to preserve the meat, and Hajjis may

now purchase a sheep from an Islamic bank to be

sacrificed in accordance with Islamic practice,

with the meat then distributed to the poor

throughout the Muslim world. Increasing numbers

of Hajjis are choosing this option, which

combines piety with charity.

Providing

Zamzam water for so many Hajjis is a major task.

Traditionally, the Zamzamis roamed the Haram

Mosque providing water to all who asked. But

with so many pilgrims today, they must now store

the water well in advance, replenish portable

containers and paper cups in numerous,

strategically located places around the mosque,

and continuously refill them as needed. A

charitable foundation also bottles Zamzam water

for sale throughout the world.

To meet

these administrative needs, the Saudi government

has established a combination of public services

and government regulated privately administered

Hajj services:

The

Hajj Private Service Industry

For

centuries, Hajj administration was largely in

the hands of ancient, family-organized guilds

that arranged for food, lodging and

transportation, and also guided pilgrims through

the Hajj rites: Wakils, or Agents, who guided

them to Makkah, usually from the nearby port

city of Jiddah; the Mutawwifs (from the word

Tawaf), who guided Hajjis through the Hajj

rites; Zamzamis, who distributed Zamzam water;

and Dallils, or Guides, who guided visitors to

al-Madinah. Lacking the resources to take over

these tasks, King Abd al-Aziz ("Ibn Saud")

left them in the hands of the guilds. As the

Hajj was the backbone of the economy of the

Hijaz, the guilds had traditionally charged

literally whatever the Hajj traffic would bear.

However, the Saudi government, which takes its

responsibility as custodian of the Two Holy

Places very seriously, strictly regulates the

guilds in order to insure that the Hajjis not be

overcharged. Today, the guilds function much as

public utilities. To the present day, the

principal responsibility for providing personal

services to the Hajjis rests with the Mutawwifs,

who act essentially as religious tour guide

companies for designated countries of origin.

They are responsible for looking after the

Hajjis under their care from the time they leave

home for Saudi Arabia until they return home

again.

The

Hajj service industry also includes other

regulated private sector enterprises. Overland

bus transportation is provided by a combination

of foreign and Saudi public and private

companies. Of the 11,5000 buses in service in

the 2002 Hajj, the Saudi Transportation

Syndicate, made up of several private companies,

provided 7,000, and the Saudi Arabian Public

Transportation Company (SAPTCO) provided 600.

SAPTCO is a publicly traded, government-managed

company whose board of directors is chaired by

the Undersecretary of Communications. It was

created 24 years ago to provide bus scheduled

intercity and international service and

chartered service for the Hajj and Umrah. The

rest of the buses come from foreign countries.6

In

1945, Saudi Arabia established Saudi

Arabian Airlines (Saudia) as a national

air carrier. In addition to providing

domestic and international air service,

it was also given the mission to provide

service "for Moslems on pilgrimage

to the Holy Cities of Islam in Saudi

Arabia."7

In the 2003 Hajj, Saudia plans to carry

893,702 Hajjis on 1,754 flights from 70

international destinations.8

Most Hajjis will enter the Kingdom at

Jiddah, the main Hajj port of entry,

where two special Hajj air terminals

await them, the largest structures under

a single roof in the world.

In

1945, Saudi Arabia established Saudi

Arabian Airlines (Saudia) as a national

air carrier. In addition to providing

domestic and international air service,

it was also given the mission to provide

service "for Moslems on pilgrimage

to the Holy Cities of Islam in Saudi

Arabia."7

In the 2003 Hajj, Saudia plans to carry

893,702 Hajjis on 1,754 flights from 70

international destinations.8

Most Hajjis will enter the Kingdom at

Jiddah, the main Hajj port of entry,

where two special Hajj air terminals

await them, the largest structures under

a single roof in the world.

Public

and private Islamic foundations also are

involved in operations such as providing and

distributing sacrificed meat and Zamzam water.

The Ministry of Awqaf (Islamic foundations;

sing. Waqf)) also acts as a repository for those

who wish to donate charitable contributions as a

part of their Hajj experience.

Hajj

Public Services

In

addition to government-regulated and

government-owned Hajj service companies, Saudi

Arabia must also provide extensive direct

government services for the Hajj. Overall

services are coordinated by the Hajj Ministry

and the inter-agency Central Hajj Committee.

Public safety, public security and traffic

control are provided by the Ministry of

Interior, and were a special crisis to arise, it

can also call on the National Guard. It is

responsible for regulating entry and exit from

the Kingdom at all land, sea and air ports of

entry, and insuring their safe overland travel

to and from Makkah and al-Madinah. For the most

part, overland traffic is spread out over a

number of weeks, but during the Nafrah, all 2

million Hajjis set out at the same time for the

same place. It has become one of the greatest

traffic gridlocks in the world. Despite

Herculean efforts by the traffic police,

supplied with the most up-to-date equipment; the

journey from Arafat to Mina can take over 12

hours. By comparison, consider a dozen Super

Bowl games getting out at the same time and

place, everyone all heading in the same

direction.

Public

health is another Herculean task. Modern health

services were originally created in the 19th

century because of fear in Europe and America

over the spread of cholera. Asian Hajjis brought

cholera to Makkah, and North African Hajjis

spread it from there to Europe and America. The

Western powers pressured the Ottoman sultan to

create an international organization called the

Paris Office of Hygiene to oversee the health

and sanitation aspects of the Hajj. After World

War II, the newly formed World Health

Organization assumed this responsibility after

absorbing the Paris Office. In 1956, the Saudi

Ministry of Health assumed responsibility for

Hajj health and sanitation and now operates

extensive preventative and curative health and

sanitation facilities at all major Hajj

locations.9 The

Saudi Red Crescent Society also participates,

operating first aid and other facilities.

Of

lesser magnitude but equally important,

personnel in Saudi Embassies and Consulates

abroad must be augmented each year to process

foreign Hajj visa applications. At home, the

Foreign Ministry also plays host to VIPs making

the Hajj, including cabinet ministers, heads of

state and other important personages.

Hajj

Infrastructure

The

government has also spent billions of dollars on

Hajj infrastructure. This has included major

expansions of the two holy mosques in Makkah and

al-Madinah. The Haram Mosque can now comfortably

accommodate a million worshipers, and during the

Hajj, twice that number pack into it. There are

also two new levels to increase capacity for

performing the Sa`y. The Prophet's Mosque in al-Madinah has also been expanded, although the

crowds are smaller there during the Hajj.10

In Mina, the space for throwing stones at the

three Jamras has been increased to three tiers.

To

accommodate overland transportation at the Hajj,

the Saudi government has constructed hundreds of

miles of all weather, four lane highways,

particularly between Arafat and Mina. It has

also installed created a fully computerized

traffic control system. Each year, portable tent

cities are set up at `Arafat and Mina to provide

housing, food, water, health and sanitation,

transportation, telecommunications, public

safety, banking facilities, markets - indeed all

amenities of a city of 2 million people. All in

all, nearly every Saudi government agency and

ministry becomes involved one way or another in

making the Hajj an administrative success.

The

Political Significance of the Hajj

The

Saudi government has always maintained a strict

policy banning political activity under the

pretext of attending the Hajj, welcoming Muslims

regardless of their political persuasion.

Nevertheless, over the years there have been a

number of political activists that have tried to

use the occasion to press their political

agendas. During the height of Arab socialism,

radical Arab nationalists made periodic attempts

to embarrass the Saudi regime by disrupting the

Hajj, but none of them were successful. In an

attempt to challenge Saudi Arabia's role of

leadership in the Muslim world and discredit its

custodianship of the Islamic holy places, the

Khomeini regime in Iran sent provocateurs to

disrupt 1982 Hajj in an attempt. Tensions

mounted in subsequent years, until 1987 when 400

people were killed and Saudi security services

had to be called in to quell violent agitation

by Iranian Hajjis.11

Muslims throughout the world condemned the

agitation as a desecration of the Hajj.

Since

then, the Hajj has remained a peaceful and

joyous occasion as it was intended to be.

However, in the wake of the attacks on September

11, 2001, the threat

of violent political activity has increased as

militant Muslims put forward the claim that

anti-American and anti-Zionist demonstrations

would be in the name of Islam, not politics.

The

Economic Impact of the Hajj:

Prior

to the oil era, the Hajj was the economic

backbone of the Saudi economy. With vast oil

wealth, the government no longer depend on Hajj

revenue, but it is still a major source of

income for the private sector. In addition to

the Hajj service industry, the Hajj is a major

season for the consumer retail season as well,

somewhat analogous to the Christmas season in

the United States. Hajjis from third world

countries in particular buy items that are hard

to get or highly taxed at home, such as

medicines and luxury items such as perfumes and

jewelry. For the 2003 Hajj, about 1500 young

Saudis have been hired and trained to accompany

the Hajjis on their sacred journey. According

the project director, the aim of the project is

to create employment for Saudi youth while

helping guests and serving in the worship of

God.12

In

recent years, Islamic religious tourism has been

expanded far beyond the Hajj. Many Muslims from

all over the world now perform the Umrah year

round. The fasting month of Ramadhan is

particularly busy season, as many Saudi

residents also flock to the Holy Places. At the

month draws to an end, Muslims celebrate the

anniversary of the first revelation of the

Qur'an. On this lailat al-qadir, or "night

of power," some three million people

perform tarawih prayers in the Haram Mosque,

more than at the Hajj.13

With

year round visits now to the two Holy Places,

there are no published figures that break out

gross revenues generated by the Hajj, but they

are estimated to be in the billions of dollars,

including annual government expenditures.

The

Social Impact of the Hajj

In its

size and global scope, the Hajj is the greatest

single ritual celebration, not just of Islam,

but of any religion anywhere. As one of the Five

Pillars of Islam, it is an obligation for

one-fifth of world's population. During the

month of Dhu al-Hijjah, virtually the entire

population of Saudi Arabia is intimately touched

by the Hajj, whether directly in its

administration, its service industry, as a

purveyor of personal goods and services, or

indirectly by observing it on television. The

`Id al-Adha, observed at the end of the Hajj, is

celebrated throughout the Muslim world as a time

of worship and fellowship with family and

friends.

Unlike

the impact of the Hajj on many foreign visitors,

whose journey is a mystical, once in a lifetime

experience, the Saudi experience while visiting

the Islamic Holy Places, during the Hajj or at

any other time of year, is a local, accessible

reality. The sites are the physical and

geographical manifestation of the birth of

Islam. This blending of the highly sacred and

the familiar commonplace has permeated Saudi

society to such an extraordinary degree that it

can be felt in virtually every human endeavor

from politics to business to simple recreation.

Notes:

1.

The other pillars are the Shahada, or Profession

of Faith: "There is no god but God and

Muhammad is the Prophet of God"; Salah:

regular prayer five times a day while facing

Makkah; Zakat: charitable giving; and Sawm:

fasting from sunup to sundown during the Muslim

month of Ramadhan.

2. The Muslim, or Hijriyyah

calendar, designated "AH," began on

July 16, 622. Its lunar years are eleven days

shorter than the solar year, resulting in the

Hajj beginning earlier each solar year.

3. It is important to note that

this description is highly abbreviated. The

actual rites are somewhat more complicated and

include numerous variations and details.

4. The Saudis were actually in

control of Makkah in 1925, and allowed to

perform the Hajj, though numbers were greatly

reduced.

5. Long, The Hajj Today, p. 135.

Figures are derived from collating multiple

sources.

6. The Saudi Arabian Information

Resource, 18 December 2002,

(http://www.saudinf.com/main/y5068.htm

).

7. Saudi Arabian Airlines,

"The Story of Saudi Arabian Airlines,"

(pamphlet, 1970), pages unnumbered.

8. Ibid. 6 January 2003, ( http://www.saudinf.com/main/y5159.htm

).

9. See David E. Long, The Hajj

Today, (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1979), pp.

76-87.

10. Greg Noakes, "The

Servants of God's House," Aramco World,

January/February 1999, pp. 48, ff.

11. John L. Esposito, "The

Iranian Revolution: A Ten Year

Perspective," in John L. Esposito, ed., The

Iranian Revolution: Its Global Impact, (Miami:

Florida International University Press, 1990),

pp. 34-35.

12. Saudi Arabian Information

Resource, 14 January 2003, ( http://www.saudinfo.com/main/y5204

)

13. Noakes, Loc. cit.

| About

the Author |

|

David

E. Long

is a consultant on Middle East and Gulf affairs

and international terrorism. He joined the U.S.

Foreign Service in 1962 and served in Washington

and abroad until 1993, with assignments in the

Sudan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. His

Washington assignments included Deputy Director

of the State Department's Office of Counter

Terrorism for Regional Policy, a member of the

Secretary of State's Policy Planning Staff, and

Chief of the Near East Research Division in the

Bureau of Intelligence and Research Bureau. He

was also detailed to the Institute for National

Strategic Studies of the National Defense

University in Washington, 1991-92, and to the

United States Coast Guard Academy, 1989-91,

where he served as Visiting Professor of

International Relations and in 1990-91 as Acting

Head of the Humanities Department. David

E. Long

is a consultant on Middle East and Gulf affairs

and international terrorism. He joined the U.S.

Foreign Service in 1962 and served in Washington

and abroad until 1993, with assignments in the

Sudan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. His

Washington assignments included Deputy Director

of the State Department's Office of Counter

Terrorism for Regional Policy, a member of the

Secretary of State's Policy Planning Staff, and

Chief of the Near East Research Division in the

Bureau of Intelligence and Research Bureau. He

was also detailed to the Institute for National

Strategic Studies of the National Defense

University in Washington, 1991-92, and to the

United States Coast Guard Academy, 1989-91,

where he served as Visiting Professor of

International Relations and in 1990-91 as Acting

Head of the Humanities Department.

A

native of Florida, he received an AB in history

from Davidson College, an MA in political

science from the University of North Carolina,

an MA in international relations from the

Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Ph.D.

in International Relations from the George

Washington University.

In 1974

-1975, Dr. Long was an International Affairs

Fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations and

concurrently a Senior Fellow at the Georgetown

University Center for Strategic and

International Studies. While on leave of absence

from the State Department, he was the first

Executive Director of the Georgetown University

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, 1974-1975.

In 1982-1983, he was a Senior Fellow of the

Middle East Research Institute and Adjunct

Professor of Political Science at the University

of Pennsylvania, and in 1987-1989, he was a

Diplomat in Residence and Research Professor of

International Affairs at Georgetown.

Dr.

Long has been an adjunct professor at several

Washington area universities, including

Georgetown, George Washington and American

Universities and the Johns Hopkins University's

School of Advanced International Studies. He has

also lectured extensively in the United States

and abroad on topics relating to the Islam, the

Middle East and terrorism.

His

publications include The Government and

Politics of the Middle East and North Africa

(co-editor with Bernard Reich, 4th ed. 2002), Gulf

Security in the Twenty-First Century

(co-editor with Christian Koch, 1998), The

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1997), The

Anatomy of Terrorism (1990), The United

States and Saudi Arabia: Ambivalent Allies

(1985), Saudi Arabian Modernization (with

John Shaw, 1982), The Hajj Today: A Survey of

the Contemporary Makkah Pilgrimage (1979), Saudi

Arabia (1976) and The Persian Gulf

(1976, revised 1978).

|

The

Hajj - SUSRIS NID - January 4, 2006

The

Hajj in Perspective: A Conversation with David Long - SUSRIS

Interview - Jan 23, 2005

Pilgrims

Bid Farewell to Makkah - SUSRIS IOI - Jan. 25, 2005

A Hajj Diary - By Faiza

Saleh Ambah - SUSRIS IOI: